Tags

Childhood Memories, Depression, Fear, Francisco Goya, Grandparents, Los Caprichos, Mental Health, Monsters, Panic, Phobias, Somatic Responses, The Empire State Building

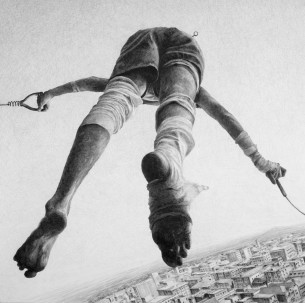

In 1977, my grandparents took me and my sisters to the top of the Empire State Building. I can remember being annoyed by all the waiting in line just to ride the elevator to the observation floor. We probably spent more time waiting to board that elevator than we spent viewing the view. Still, when our turn came around and after the elevator finally reached the 102nd floor, I burst out of the doors to see what all the fuss was about.

In 1977, my grandparents took me and my sisters to the top of the Empire State Building. I can remember being annoyed by all the waiting in line just to ride the elevator to the observation floor. We probably spent more time waiting to board that elevator than we spent viewing the view. Still, when our turn came around and after the elevator finally reached the 102nd floor, I burst out of the doors to see what all the fuss was about.

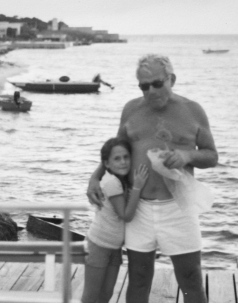

At first, I was too distracted with taking in the view to notice that my grandpa was not with me. When I turned back to search for him, I saw that he had parked himself close to the elevators away from the windows and the view. I called to him, “Grandpa, you gotta come see this.” “No thanks,” he replied “I’m good here.” “Pretty please,” I pleaded. This time he just smiled at me as he shook his head, still refusing to budge.

My grandfather could be ridiculously stubborn and occasionally quite fierce. He was a brusque and burly man with large, pudgy-fingered hands that were both soft and strong. Even though he was often stern, at times he would go out of his way to be loving. He taught me to fish and how to use the heels of my feet to dig for clams in the bay at low tide. He liked to tell his granddaughters that he would do anything for us. He used to say, ” You know, I’d give you the shirt off my back.” And he meant it. While I didn’t exactly covet his dirty, greasy-food stained shirts, I knew that he was saying he loved me.

My grandfather could be ridiculously stubborn and occasionally quite fierce. He was a brusque and burly man with large, pudgy-fingered hands that were both soft and strong. Even though he was often stern, at times he would go out of his way to be loving. He taught me to fish and how to use the heels of my feet to dig for clams in the bay at low tide. He liked to tell his granddaughters that he would do anything for us. He used to say, ” You know, I’d give you the shirt off my back.” And he meant it. While I didn’t exactly covet his dirty, greasy-food stained shirts, I knew that he was saying he loved me.

When my grandfather refused to come see the view, I was confused. So, I went back to where he was standing and asked him why. “I’m afraid of heights” he admitted. “And while you were peering down a hundred floors to the ground, my toes were curling under trying to grip onto something sturdy and safe.”

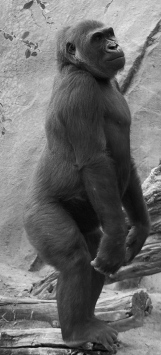

I am guessing that until that day I had never thought about my grandfather’s feet before. After he explained the “why,” though, I did not picture human feet. Instead, the first image that came to mind was of a huge chest-pounding gorilla, who—in failing to wrap his long, fat, hairy toes around something substantial—was inadvertently digging his sharp nails into the flat wooden floorboards beneath his feet.

I am guessing that until that day I had never thought about my grandfather’s feet before. After he explained the “why,” though, I did not picture human feet. Instead, the first image that came to mind was of a huge chest-pounding gorilla, who—in failing to wrap his long, fat, hairy toes around something substantial—was inadvertently digging his sharp nails into the flat wooden floorboards beneath his feet.

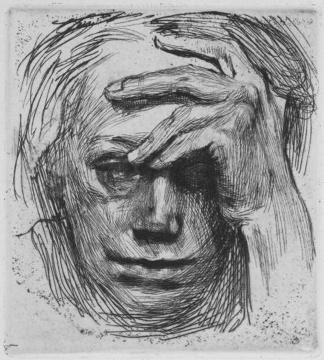

I had not thought much about that image since then, until it reappeared recently. Somehow, my subconscious had linked the image of those gripping gorilla toes to the famous work of art by Francisco Goya titled The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.

This self-portrait of Goya’s is probably the most well-known of the 80 etchings in his Los Caprichos (The Caprices) series, and I have seen it many times before. Even so, the “production” of monsters was not really something that I had considered in any depth. When my mind paired Goya’s portrait with the “portrait” from my imagination, though, I started to contemplate the ways that monsters develop and form and I began to wonder about the people who create them.

The monster for my grandfather was born of his fear of falling. Without knowing it at the time, I must have understood that my grandfather had created this monster and that in essence he  was the monster. He became a huge gorilla, getting in his own way. In the etching, Goya animates his fears for us, and with the title he acknowledges that we lose our ability to protect ourselves from fear when our logical thought processes are somehow turned off or malfunctioning. Without access to reason or when reason cannot communicate effectively with the other parts of the brain, things that are normally benign or nonthreatening can transform into things that are frightening and alarming.

was the monster. He became a huge gorilla, getting in his own way. In the etching, Goya animates his fears for us, and with the title he acknowledges that we lose our ability to protect ourselves from fear when our logical thought processes are somehow turned off or malfunctioning. Without access to reason or when reason cannot communicate effectively with the other parts of the brain, things that are normally benign or nonthreatening can transform into things that are frightening and alarming.

My grandfather did not feel a little wobbly just thinking about his distance from the ground; he was terrified and literally gripping with fear. The risks entailed in this trip to the top of a skyscraper were minimal, but his toes did not see it that way. From their perspective, my grandfather needed to be afraid, stay back, and hold on for dear life.

Toe curling, chest tightening, stomach rumbling, crying, and so on are all automatic physical responses that come from a part of your brain that works unconsciously and quickly. Those physical sensations in your body act as messages telling the slower, deliberative part of your brain that you are, for example, tired, hungry, sad, or in danger.

This is not to say that your conscious brain cannot affect and change those sensations. Ideally, the cognitive part of your brain uses reasoned logic to assuage any irrational worries that the faster part has identified as areas of concern (for example, the 102nd floor of the Empire State building is virtually as safe as the second floor). However, if the communication between these two areas of the brain isn’t working so well, or if there are particular kinds of experiences that seem to gum up the system, then your somatic responses might continue to send your conscious mind warning messages despite the lack of threat. If panic signals such as shallow breathing, a racing heart, or curling toes keep flashing despite logic, then the threat becomes irreducible and seems real.

Ideally, the cognitive part of your brain uses reasoned logic to assuage any irrational worries that the faster part has identified as areas of concern (for example, the 102nd floor of the Empire State building is virtually as safe as the second floor). However, if the communication between these two areas of the brain isn’t working so well, or if there are particular kinds of experiences that seem to gum up the system, then your somatic responses might continue to send your conscious mind warning messages despite the lack of threat. If panic signals such as shallow breathing, a racing heart, or curling toes keep flashing despite logic, then the threat becomes irreducible and seems real.

I am sure my grandfather tried to convince himself that there was nothing to fear. In that moment, though, logical analysis did not pacify his nerves or calm his toes. It was not laziness, or weakness, or lack of resolve that petrified my grandfather. There was just some sort of breakdown in the communication between the various parts of his brain, like a feedback loop not connecting in the ways that it should.

As someone who has struggled with a malfunctioning brain, I find Goya’s idea of “sleeping reason” reassuring, especially when I couple it with an image of a reflexive somatic response to fear. Even though I am very familiar with the process of sinking into a deep depression, I still always hope that this time will be different; this time I will make it stop before it grabs hold. Sometimes, though, “my toes” are going to “curl under” whether I want them to or not. Sometimes, my brain will create “monsters” that aren’t really there. Telling myself repeatedly that it isn’t happening or blaming myself for not being able to fix the problem on my own is unproductive.

As someone who has struggled with a malfunctioning brain, I find Goya’s idea of “sleeping reason” reassuring, especially when I couple it with an image of a reflexive somatic response to fear. Even though I am very familiar with the process of sinking into a deep depression, I still always hope that this time will be different; this time I will make it stop before it grabs hold. Sometimes, though, “my toes” are going to “curl under” whether I want them to or not. Sometimes, my brain will create “monsters” that aren’t really there. Telling myself repeatedly that it isn’t happening or blaming myself for not being able to fix the problem on my own is unproductive.

Perhaps in the future, when a severe episode of depression seeps back in and I find myself overwhelmed and sickened by the prospect of getting out of bed, showering, or even just brushing my teeth, I will be able to picture my two images of fear. I will probably still look for ways to escape and still feel that I cannot find myself. And in all likelihood, I will still worry about all the “shoulds.”

When depression flares up again and I sense a coldness that I cannot warm and I feel myself shivering and shaking inside with my teeth chattering and my skin pebbling, almost certainly I will still think that it should not be this way. I will think of how it is summer, how the sun is shining, and how good it feels to have warming light all around me, and I will tell myself that I should be able to experience all of that. But when I cannot make myself believe in a warmth that I cannot feel, maybe I will think of my grandfather’s feet or Goya’s monsters, and I will forgive myself.

Reblogged this on trips take people.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on RussDOMED.

LikeLike

Your heartfelt story about the feeling of helplessness that brain chemistry conjures up in many individuals certainly will help many who may feel alone with their affliction. My interest grew as you did a masterful job weaving your relationship with your grandfather and his particular fear and your own personal everyday battle. Thank you for enlightening us.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for reading and commenting. Your kind words are reassuring. I really appreciate your taking the time to let me know your thoughts.

Best,

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing words!

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | topschannelblog

Thank you for reposting my work.

LikeLike

Your grandfather did something particularly difficult for himself in order for you to have the experience on 102nd floor. Kudos to him.

LikeLike

You are right. He wanted to do what he could for his grandchildren.

Best,

Francesca

LikeLike

Loved it

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please dont hesitate to check out my blog and follow me.. Thank you

LikeLike

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | tmz2016

Thank you for sharing my post.

LikeLike

Found your blog today, lovely read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you liked it. Thanks for reading.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | flowdeep

Thank you for reposting this piece.

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike

You’re welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a very good piece, and coincidentally I have an awful fear of heights too. Do you mind if I translated this to Indonesian and put it in my blog instead? i’ll linked it here and with your name attached as the original writer, of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for translating and sharing my work.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | BM LUCAS2 C´sh

Thank you for sharing this post.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on 𝓬𝓸𝓬𝓸𝓵𝓸𝓾𝓲𝓼𝓮89 and commented:

This is simply beautiful, I feel like I’m in the moment with the author.

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind words and for sharing the work.

Best,

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | Anarchic Mayhem

Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Uniquely writing in its entirety, I enjoyed it!

LikeLike

It’s nice to know that you enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing this awesome piece of your story.

~Kah Choon

LikeLike

You are very welcome.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | oshriradhekrishnabole

What u wrote is amazing , the last part is astonishing ..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading and your generous feedback.

LikeLike

Amazing

LikeLike

Thanks.

LikeLike

So touching 😢

LikeLike

Lovely. Pure emotions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Production of Monsters | barkinet2016

Thanks for sharing my post.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Still Another Photoblog.

LikeLike

I love love love this post. Wonderful post.

LikeLike

Thank you for letting me know how much you liked it.

Best,

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful narrative. Somehow I found it inspiring and helpful.

Well the fear was real, so is the everyday battle.

Thank you for your deep insight.

regards,

LikeLike

I am so glad to hear that you found this post helpful.

Take care,

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an amazingly well written post!

LikeLike

That is very kind of you to say. Thank you.

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLike

“Even though I am very familiar with the process of sinking into a deep depression, I still always hope that this time will be different; this time I will make it stop before it grabs hold. Sometimes, though, “my toes” are going to “curl under” whether I want them to or not. Sometimes, my brain will create “monsters” that aren’t really there.”

Yes. Just yes. Thank you for sharing and finding the words I’ve been searching for for so long.

LikeLike

I’m so pleased that my words rang true for you. Thank you for reading and commenting.

Francesca

LikeLike

Great article

LikeLike

Thanks.

LikeLike

Lovely post. How you narrated your Grandpa’s tale to a picture and eventually depression is marvellous piece of writing. Thank you for sharing this.

LikeLike

That is really kind of you to say. Thank you.

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations, my lovely friend, your blog is so interesting and inspiring.

Therefore, I have decided to nominate you for the One Lovely Blog Award

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the encouragement.

Best,

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

All the best, Francesca.

LikeLike

An inspiring post . ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you thought so.

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great post. Thank you for your hard work and talent.

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and for letting me know that you liked it.

Francesca

LikeLike

Hello 🙂

We would love to feature ‘The Production of Monsters’ on Kindness Blog with links back to you.

Would that be OK? No problems if not 🙂

Best, Mike.

LikeLike

Hi,

Thank you for asking about sharing my post. I really appreciate your interest and your considerate approach to honoring authorship. If you would still like to feature my post on your site, please feel free to do so. I am always grateful for the opportunity to reach more people who might find the post helpful or interesting.

Best,

Francesca

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Francesca! We’ve just gone live… 🙂

Best, Mike.

LikeLike